Chapter II

Chapter I-Chapter III

- By

- Nathaniel Minor

- Rachel Estabrook

- Ben Markus

What happens after a revolution?

If you’re on the winning side, as Douglas Bruce of Colorado Springs was 25 years ago, you take a victory lap. If you were one of the politicians who’d lost, you try to figure out what comes next.

Both scenarios played out in the basement of the state Capitol weeks after the 1992 election. Lawmakers, lobbyists and others learned from Bruce himself that his Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights, which was sold as a means to give voters the final say on all tax increases, entailed much more. It also contained mechanisms that cut off other methods of raising revenue.

— Rick Reiter

“As Bruce went over the measure in excruciating detail, members of the audience wore looks of amazement as the full sweep of the truth dawned on them,” The Denver Post wrote in late November 1992. “Bruce obviously had thought deeply about every phrase in the amendment and anticipated almost all of the possible escape routes traditionally favored by public officials.”

After spending more than five years and thousands of his own dollars trying to push TABOR across the finish line, it was a sweet moment for Bruce. He held court for two and a half hours. “They weren’t audibly groaning,” Bruce said a quarter century later. “But you could tell they didn’t like the fact that some upstart from Colorado Springs was laying down the law, literally.”

Public officials around the state were now ensnared in Bruce’s maze. And it would take them a while to find a way out.

In the years following TABOR’s passage, nearly everything went according to plan. Government tax revenue grew rapidly as Colorado emerged from the recession that dogged the state through the 1980s. And, just as Bruce had designed it, TABOR kicked in and prevented the government from growing as quickly as the economy. Refunds were the order of the day — the state returned more than $3 billion between 1997 and 2001.

Bruce achieved extraordinary fame for someone who didn’t hold political office. A staggering 70 percent of Coloradans knew who he was, according to a 1995 poll from political consultant Floyd Ciruli. He was hugely influential — at least for a while.

“There was not a single Republican who ran for office who did not go sit at the feet of Doug Bruce,” said Rick Reiter, a longtime Denver Democratic political consultant. Would-be politicians would come to learn about TABOR and Bruce’s vision for limiting government, Reiter said. “That was kind of a litmus test. You had to pledge allegiance to Doug Bruce because he was the personification of ‘no new taxes.’ ”

The reign would not last. Before long, politicians on the left and the right would join forces to severely weaken Bruce’s crowning achievement. And the man who helped deliver the gut punch was one of its earliest supporters.

In the late 1990s, Bruce’s Colorado was a shining city upon a hill for the libertarian movement. It had one of the strongest economies in the country while handing back excess revenue to residents, who rewarded conservatives in 1998. The GOP won the governor’s office and the statehouse for the first time in a quarter century. In 2002, the conservative National Review anointed William “Bill” Forrester Owens as the “Best Governor in America.”

Owens was being groomed for a grander spotlight, said Chris Castilian, then Owens’ deputy chief of staff. “He had been very involved in national Republican politics. He had been high profile at the RNC convention in New York in 2004. And that was all by design; it was to get him ready for that national stage.”

Owens, a Texas native, came to Colorado to work in oil and gas. Political observers nicknamed him “Woody” after the tall, handsome cowboy from Pixar’s “Toy Story.” By the time he ran for governor, after serving in the legislature and as state treasurer, his political identity had crystallized as a tax-cutting conservative. One of the original nine state lawmakers to support TABOR in 1990, he even had a certificate from Bruce thanking him for his efforts.

Colorado’s economy roared through Owens’ first term. Owens, who declined multiple interview requests, boasted at the time that he presided over more tax cuts than any governor in state history; many driven by Bruce’s constitutional adjustment. “It’s just like manna from heaven here,” one Republican legislator said during the boomtimes.

Then the economy stuttered after the Dot-Com Bust and the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. Lawmakers were faced with about $1 billion in budget shortfalls for three years straight. In 2003, more than 600 state employees were laid off and most programs saw cuts of 10 percent. Higher education took a hit, leading to big tuition increases. The University of Colorado hiked tuition by 15 percent in 2003 alone.

The recession didn’t last long, but it exposed a little-noticed provision buried in TABOR known as the “ratchet” effect. The formula dictated the government budget could only ever grow by what it spent the year before plus the change in population and inflation. When state revenues fell off a cliff, TABOR prevented them from climbing back up — even as the economy lurched back into gear.

But Owens was reluctant to make any changes to the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights. It had become Republican dogma — an untouchable, sacrosanct part of the state constitution. If Owens wanted to suspend the refunds, it would be spun as a betrayal. “Far from being a straightjacket on our economy, Colorado’s system of tax limits is actually an economic bullet-proof vest,” Owens said in his 2003 State of the State address. Then came the promise: “So long as I am governor, we will not raise taxes.”

Meanwhile, state budget writers like then-Rep. Bradley Young, a Republican from the Eastern Plains city of Lamar, were zeroing in on TABOR’s inflation-plus-population formula. Most lawmakers had the mistaken impression that the formula allowed state government to grow with the economy, Young said. The huge refunds the state issued startled him. So, in the late 1990s, he commissioned an analysis from the legislature’s research arm. The question: What if TABOR had been implemented in 1976?

The results shocked him. By 1993, the analysis found, Bruce’s amendment would have forced the state to refund somewhere between 20 and 25 percent of the general fund. The inflation-plus-population formula set the cap consistently between 1 and 3 percentage points behind the growth of the economy. Young concluded that TABOR’s purpose was to shrink government revenue. Not in raw numbers, but in relation to the overall economy. “It became clear that the economics needed to be more clearly understood,” said Young, who later authored a book on the matter.

His solution was a constitutional amendment that would have changed the formula to factor in personal income growth, not inflation. That would have allowed government revenues to grow more in line with the economy. Then-Senate President John Andrews, a fiscally conservative Republican, shot it down. “One of the benefits of TABOR is it has not allowed government to grow as fast as the economy,” Andrews told the Rocky Mountain News in 2004. “I think we are gutting TABOR. It’s too hard on TABOR.”

But Owens, the governor, was starting to have second thoughts. Late in 2004, deputy chief of staff Castilian remembers Owens looking over the latest, most dire numbers. Huge chunks of state government were in jeopardy; one potential fix was to actually close some two- and four-year colleges. Owens faced the prospect of that being his legacy.

“You could just see the entire attitude of Gov. Owens changed at that moment in time,” Castilian remembered. “And he decided at that moment that he was going to fix it.”

A deal was negotiated with Democrats to weaken TABOR. It didn’t change the inflation-plus-population formula, as Young had advocated. Instead, it implemented a new spending cap no longer tied to what the state spent the year before — only what it could have spent. That would effectively demolish the “ratchet effect.” Known as Referendum C, it also would suspend the cap for five years. It went to the November 2005 ballot.

“Two-thirds of the Republican Party were going nuts over this,” said Rick Reiter, the Democratic consultant who worked on the campaign. Reiter said Owens’ support, as painful as it was for him, was instrumental. “Sometimes the need to be a statesman supersedes the need to be the leader of your party.”

The man a Denver Post columnist had once dubbed “Governor TABOR” was leading the charge to cripple it. But as the opposition marshalled to defend TABOR, there was a notable omission in their ranks: Douglas Bruce.

Bruce’s days as a Republican kingmaker ended after years of bad publicity caught up with him. He’d long made a living as a landlord. After TABOR passed in 1992, Bruce found himself in Denver officials’ crosshairs for derelict properties. “Most of them were vacant and causing all sorts of problems in their neighborhoods,” said Alan Prendergast, a longtime Westword reporter who’s chronicled Bruce’s run-ins with the law.

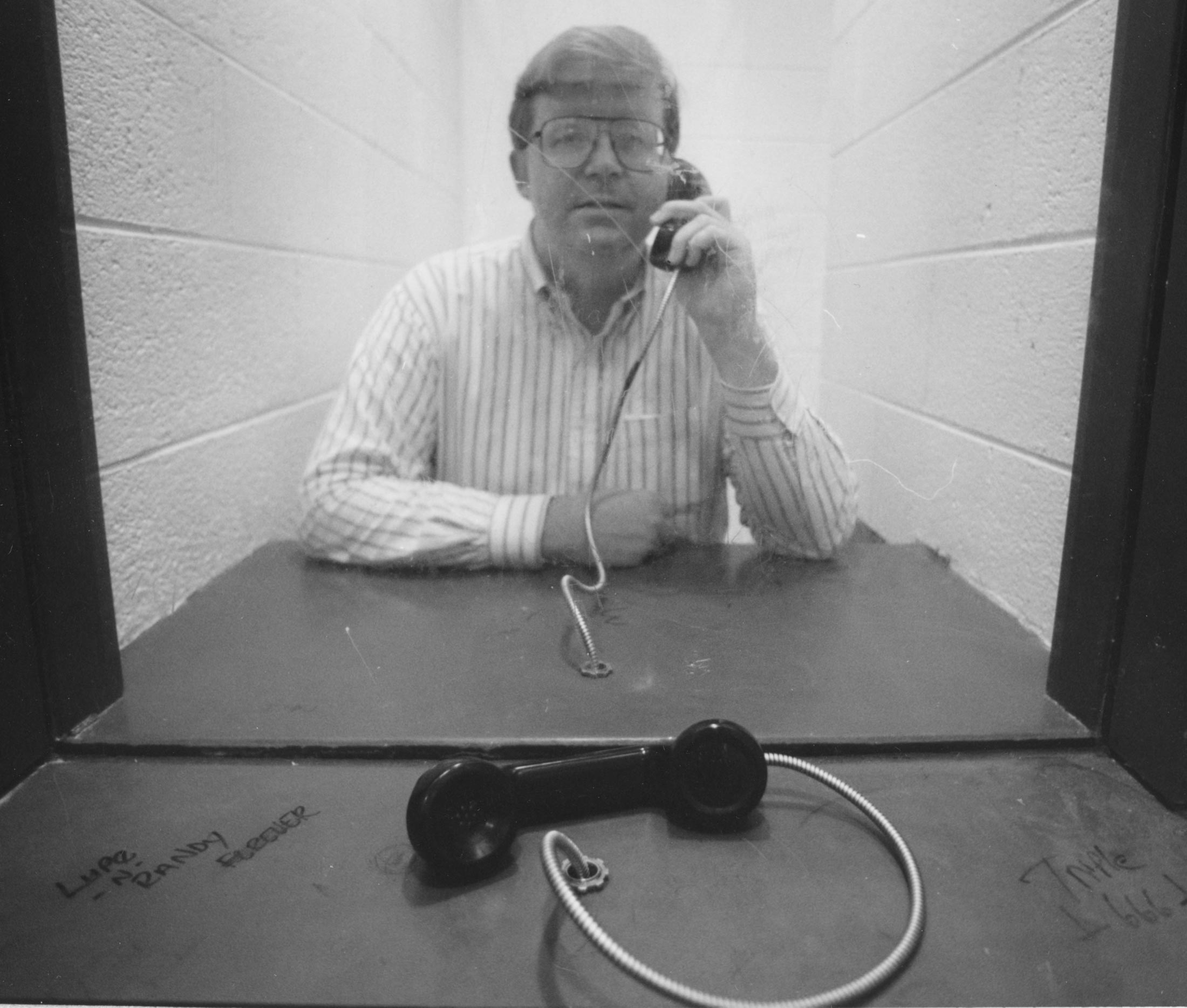

Bruce landed in court several times, and even served eight days in the Denver County Jail in 1995 for talking back to a judge. “You see how sick this is?” Bruce yelled to reporters as he left the courtroom. “They’re trying their best to make me into a criminal.” He could have avoided imprisonment, the city attorney said, had he just fixed the property in question. But Douglas Bruce is not the type to admit he’s wrong.

While in jail, Bruce compared himself to Thoreau, Gandhi, Mandela and others imprisoned for their beliefs. “I’m not saying I’m in their league,” he told a reporter for the Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph. “But the premise is the same.” He refused solid food, and survived instead on milk, water and orange juice. “He was going to show them that they couldn’t break him,” Prendergast said.

Bruce steadfastly maintains the city of Denver had a vendetta against him, a charge Prendergast believes is plausible. “You wonder whether another landlord in the same situation would’ve gone to jail,” he said. With one $523 exception, Bruce had every fine against him dismissed.

Beyond his legal troubles, Bruce had lost his touch at the ballot box. He pushed extreme anti-government restrictions at the state level year after year — and they all lost. “He’s a liability. He’s not really the savior anymore,” Reiter said of Bruce during this period. “It’s clear that his blimp is starting to run out of air.”

When the opposition to Owens’ push sought a leader, they did not go to Douglas Bruce. Instead, someone with a personality nearly as big took the reins: Jon Caldara, the brash president of the libertarian Independence Institute whose desk sits under a portrait of himself in Napoleon’s likeness.

“He does not communicate well. He does not work well with others,” Caldara said of Bruce. They kept each other at arm’s length, running parallel campaigns. Caldara also blames a left-wing conspiracy for vilifying Bruce and conflating his difficult personality with his policy and the nobility of his ideas. “He is a masterful man, he’s a good-hearted man, but he is the poster child the left wants to marry with TABOR,” he said. “They understand this art of personal destruction. And they went after Doug Bruce.”

Regardless, the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights had become bigger than the man who birthed it. National anti-tax advocates like Grover Norquist wanted to spread it across the country. A handful of national anti-tax groups descended on Colorado to save TABOR. Caldara admits they weren’t working together. The highest-profile Republican in the state, after all, was on the other side.

“Our coalition is your worst family Thanksgiving dinner ever,” Caldara said. “Everybody has their own ideas; everybody has their own reasons for doing it.”

Penn Pfiffner, a former state representative and chairman of the Tabor Foundation, said the most difficult question to answer during the campaign was: “If a conservative governor likes this, how can you be opposed?”

The pro-government campaign was well-funded, much like its corollaries were during the original TABOR campaigns in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It bought and aired one of the most iconic political advertisements the state had ever seen. John Hickenlooper, who would later become the state’s two-term Democratic governor, was then the mayor of Denver. He made the case for fixing TABOR by jumping out of an airplane over Longmont, Colorado.

It was far from a normal political ad. This wasn’t a politician strolling across a ranch with the Rocky Mountain sun gleaming off a cowboy belt buckle. But Hickenlooper didn’t relish his star turn — especially when he had to jump for a second time.

“That’s about the most terrifying thing I’ve ever done in my life,” Hickenlooper said.

The extra take proved to be worth it: The ad was quirky, and added some much-needed humor to the complex issue. Caldara knew he was in trouble. “That will go down in history as one of the great political ads in Colorado,” Caldara said, before adding, dryly: “Sadly, he had a parachute on.”

Caldara’s chief message was that taxpayers would lose out on billions in refunds. “Vote No; It’s Your Dough,” was the campaign slogan. But Caldara ran out of cash himself. He had to ditch a rebuttal ad to Hickenlooper’s jump because the campaign couldn’t afford to air it. His side was outspent two to one.

Other ways were found to get attention. Caldara painted a propane tank like a pig, put it on a trailer, and drove it around the state Capitol. He remembers that supporters even brought an actual live pig to some campaign events — a stunt that he admits backfired. “I don’t think anybody in Colorado sees government or lawmakers as pigs,” Caldara said. “That might work better in Washington. But I don’t think it worked well here. It was a bad decision.”

Referendum C, which removed TABOR’s ratchet effect at the state level and suspended spending limits for five years, passed 52 percent to 48 percent. The damage was done.

True to form, the father of the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights was devastatingly blunt with voters. “We gave the people of Colorado 13 years of freedom and the ability to hold politicians accountable,” Bruce said on election night. “They’ll have to accept the consequences of voting themselves back into slavery.”

Owens called the win a victory for Colorado, but he paid a big price. He’d spent every nickel of political capital he had to make it happen. He’d forever be labeled by conservatives as the governor who raised taxes after he promised not to. Referendum C has since allowed the state to keep more than $17 billion that would have otherwise been refunded.

“He slit his own throat,” anti-taxer Grover Norquist told the New Yorker that year. Now, Norquist points to Owens’ support of Referendum C as a big reason why no other states have enacted their own TABOR. “If Owens had fought for TABOR and held the line on TABOR and spending had been restrained ... Colorado would have been a model.” Instead, Norquist said, “Owens destroyed it.”

Owens left office in 2007 and now works at a high-powered Denver law firm. He never ascended to national political heights. Douglas Bruce’s career in political office, on the other hand, was just getting started.

Everything about Bruce suggests he’s not ideally suited for politics. He’s not inclined to compromise. He’s brash, and even he admits he’s too honest. In the mid-2000s, he hadn’t made many friends serving on the El Paso County Commission, when he compared a fellow commissioner to the Wicked Witch of the West.

Still, when a House seat opened in Colorado Springs in late 2007, Republican bigwigs chose Bruce to fill it. “I knew that it really needed some changes,” Bruce said of his mission to reconstruct government from within. “There’s no substitute for being willing to stand up against evil.”

When he arrived in 2008, Bruce didn’t waste any time making history at the state Capitol. It just wasn’t in the way he intended.

During a prayer on the day he was sworn in, Bruce kicked Rocky Mountain News photographer Javier Manzano while on the House floor. Bruce claimed it was more of a nudge — like toppling a football off a tee, as opposed to kicking a field goal. Shortly after the incident, Manzano said he was just trying to document Bruce’s professed admiration for scripture. “I didn’t expect him to kick me with a Bible in his hand,” Manzano said.

Bruce refused to apologize. “He revealed himself almost instantly,” said Vincent Carroll, a former editorial page editor for the Rocky Mountain News and Denver Post.

Predictably, the press pounced. “Bruce isn’t just a sideshow; he may be a freak show,” said a reporter for CBS Denver. Editorials railed against the new legislator. “Shape up, Rep. Bruce. And for heaven’s sake, get a grip,” The Rocky Mountain News snarled.

Lawmakers were outraged, too, and scheduled a vote of censure. Before the vote, Bruce stood up in front of his colleagues on the House floor and gave a rambling defense. He compared his plight to that of actor Jimmy Stewart in the 1939 classic “Mr. Smith Goes To Washington.” House Speaker Andrew Romanoff cut him off before he could finish. “You’re not Jimmy Stewart,” Republican Rep. Al White admonished. “This is not a 1939 movie; this is today. Your actions were wrong.”

White and nearly every other House member voted to censure Bruce, the only time the chamber had taken such a step in the state’s history. “It’s a badge of honor,” Bruce said. “These people were so saturated with corruption.”

The only lawmaker to vote against censure was then-Rep. Kevin Lundberg, now a state senator. Bruce had asked the gaggle of press around him not to take photos during the prayer, said Lundberg, who was standing nearby at the time. But Manzano kept shooting. “This nonsense that he kicked a photographer is a Capitol myth. It was a nudge with his foot,” Lundberg said. The whole incident smelled of a smear campaign, according to Lundberg. “A lot of people were out to get Douglas Bruce the very day he got here.”

Bruce made headlines again a few months later during a debate about a guest farmworker program. “I don’t think we need 5,000 more illiterate peasants in Colorado,” Bruce said, referring to Mexican immigrants. Legislators gasped. “How dare you!” said state Rep. Kathleen Curry, a Democrat.

Bruce’s behavior at the Capitol marked a turning point in how the public perceived him, said Carroll, the former Rocky Mountain News editor. While it was “remotely conceivable” to believe that the city of Denver had it out for Bruce over his rental properties, Carroll said, it was clear Bruce was sabotaging himself under the gold dome. “When it came to the incidents at the legislature, it was unfiltered,” Carroll said. “Nobody was telling you what to think. He did it, and it was crazy.”

Just a few months into Bruce’s tenure, his own party was looking to get rid of him. His seat in Colorado Springs was considered a shoo-in for Republicans. The GOP candidate did win the seat in 2010 — but it wasn’t Douglas Bruce. Mark Waller, a war veteran and a lawyer, bested him in a primary. “I kind of joked coming into the statehouse that I was one of the more well-known brand-new freshman legislators ever,” Waller said. “Not because it was me, but because I beat Doug Bruce.”

None of this appears to bother Bruce. “I don’t mind being a pariah,” he said. “If I had a choice of being silent and living another 10 years or telling the truth and living another 10 days, I’ll take the 10 days. See, there’s more important things in life than getting along with everybody.”

Bruce’s time at the Capitol made public what political insiders already knew: He’s far better at attacking the system from the outside. So that’s what he went back to. But his new battles would get him in far greater trouble than anything he’d experienced before.

Next: Douglas Bruce: “There is nobody like me.”

- -